Long-term effects and psychological impact of disasters (Tai Po fire & Grenfell fire)

中文摘要 (If you are in need of support after the fire, please find this link for the latest support available to affected residents.)

Post-Disaster Trauma: Insights from the Tai Po Fire and Grenfell Tower Fire

News and footage of the Wang Fuk Court fire in Tai Po rippled through the screens and minds of the public on November 26, 2025. The city and its government immediately responded with resource and assistance for the surviving residents of this catastrophic incident, providing both immediate relief and promises of remedial actions to care for this aching community. Local NGOs and mental health communities also rushed to provide psychological care for the impacted public, understanding the potential mental burden individuals might be forced to face after encountering this tragedy.

While urgent care was provided to the residents, the mid- to long-term issues with resettling, financial burdens, workplace accommodations, and uncertainty about the future might continue to weigh on these families. Notwithstanding the complexities of experiencing loss and/or dealing with PTSD, there is a need to consider how these residents will be adjusting in this limbo period. This post will draw on research resulting from a similar event in the UK - the 2017 Grenfell Tower fire, where the scale of destruction and failure also resulted in the displacements of hundreds of residents, with a years-long recovery process for the affected individuals. Much of the information below are from reports that include interviews and views of the Grenfell residents themselves.

Direct and Indirect Psychological Impacts

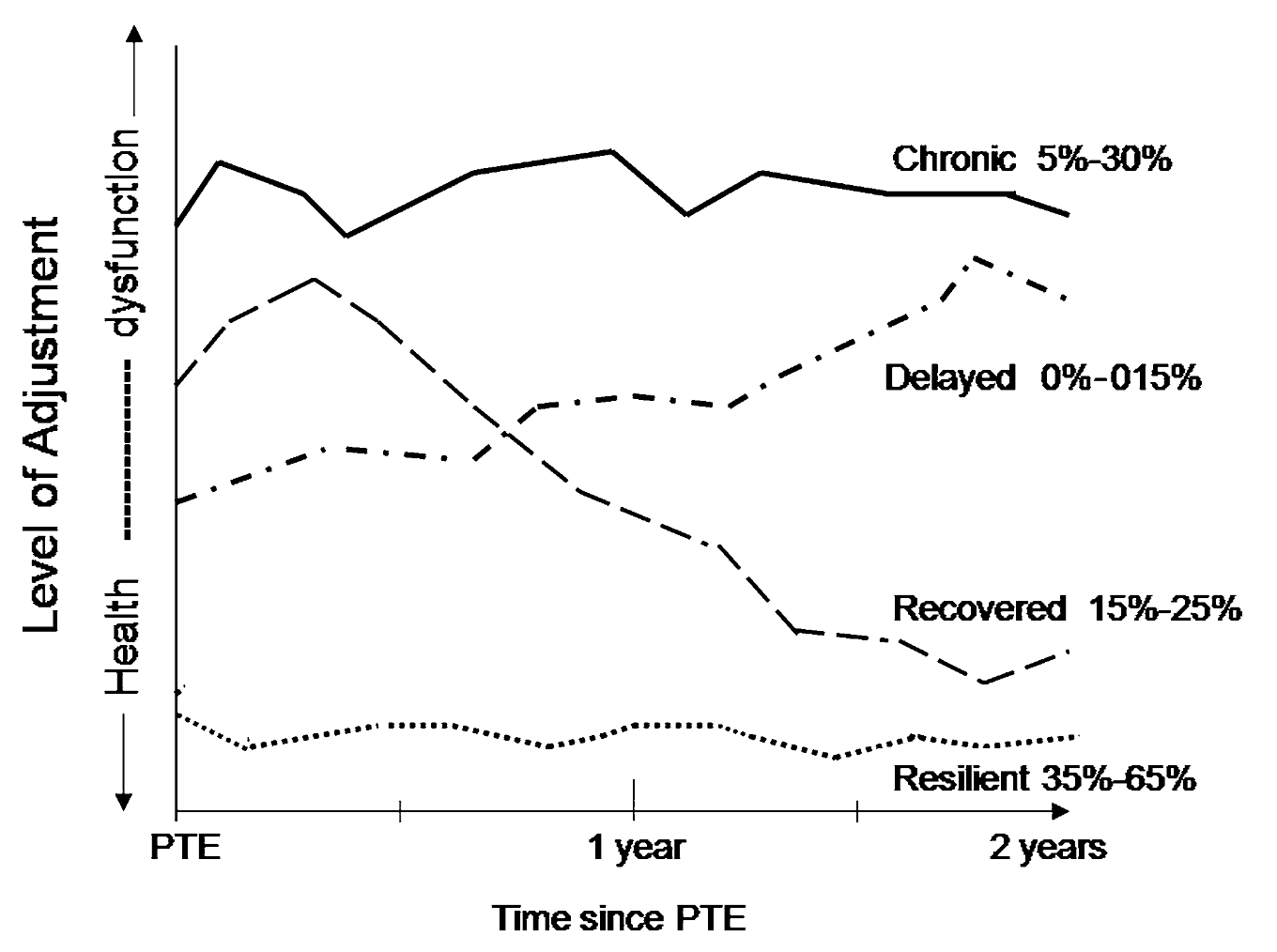

Past research has shown how survivors of traumatic events may experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression (1, 2). In Grenfell's case, a 2018 report by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea (where Grenfell Tower was located) revealed that a substantial portion (67%) of the affected adult population were identified to be at risk of PTSD and will require treatment. This magnitude was significantly beyond NHS estimation that 1 out of 3 people who experienced trauma suffer from PTSD (See also graph below for prototypical trajectories for potential traumatic events [PTE] over time). For local population who weren’t in the tower and did not need to evacuate, the risk of PTSD was 26-48% at the time. How did these populations fare over time?

(Graph from Resilience to Loss and Potential Trauma by Bonanno, Westphal, Mancini, 2011, illustrating prototypical trajectory of recovery for a population following potentially traumatic experiences. As shown, while a majority would be resilient against traumatic events, some may experienced delayed responses, while others with pre-existing conditions may be affected for longer.)

Although exact recovery rates from PTSD amongst residents are not readily available, many affected individuals continued to use emotional and mental health support services in subsequent years (~500 open cases in 2025), with higher utilization observed amongst women and youths, demonstrating the stability and suitability of these services for the local population over time. Through interviews and research in these services, NHS’ follow-up reports from subsequent years also identified three main areas of concern for these affected populations: the impact of trauma on children, issues with mental health services, and long-term changes experienced by residents.

Parents reported that their children suffered panic attacks, displayed regressive behaviours (for example, bed-wetting) or delayed traumatic responses (ex. nightmares after a few months), and, in the case of adolescents, displayed growing aggression or reluctance to seek help. These effects were showing up immediately or even a year after the fire.

Residents expressed reluctance to pursue counselling due to stigma around PTSD diagnoses, limited understanding of mental health terminology and needs, and language or cultural barriers when accessing GP or mental health services.

Finally, for residents who have been displaced following the fire, they described difficulties adjusting to the sudden loss of home and community, resulting in feelings of isolation. This was exacerbated by the lack of certainty on future resettlement, with some moving into hotels or other temporary accommodations, leading to other challenges like lack of privacy or increased distance from schools and work (approximately 204 households had to be relocated, with 199 finally permanently rehoused in 2024). Past research in the UK have shown psychosocial distressed being linked to relocation after a disaster, so similar effects may be affecting the Grenfell victims as well.

Many people did find the mental health services helpful, especially when language and cultural barriers were addressed through interpreters and culturally sensitive providers - changes that depended on authorities listening to residents’ needs. Counselling primarily focused on addressing issues related to depression, PTSD, and anxiety, with the latter two becoming increasingly prevalent over the years. There was also increasing support for community-led self-care initiatives - for example, cooking classes, women-only yoga, men’s activity groups, and monthly silent walks to mourn losses, which engaged the community and offered alternatives for those who preferred not to use formal mental health services.

(Read more about these services and interviews in reports by the NHS here.)

Yearning For Justice

While the physical and psychological needs were addressed, there was a continuous yearning for justice and change after the fire. Prior to the disaster, residents have already requested investigation into the lack of safety features in the building. The community also felt neglected in the immediate aftermath of the fire, with local groups and organizations pooling resources together until the regional authorities eventually sent support. These series of disappointments fuelled the initial distrust against authorities who were subsequently sent out to help the residents, including the mental health support initiative started by regional authorities.

These frustrations also spurred community-led efforts like Grenfell United, which advocates for victims’ justice by demanding clarity and accountability in the disaster and ensuing government inquiries, while highlighting safety issues affecting other social housing residents. Nonetheless, a recurring experience in the years that followed was a deep sense of helplessness. Many felt their community’s warnings had been disregarded before the tragedy, and others felt sidelined in later government inquiries - reviving earlier distrust. That distrust also spread to residents of other social housing blocks, who had been waiting for safety upgrades after the inquiry and continued to face uncertainty about their safety and possible relocation, years on from the fire.

Pathways to recovery for Hong Kong

In the months and years following the Tai Po fire, residents’ experiences may mirror those of Grenfell survivors. Feelings of uncertainty and hopelessness may develop, and residents may feel unsure about next steps, as they face questions about permanent relocation, loss of community, changes in work or school, and, for some, the grief of losing family members. Feelings of isolation may be heightened by the city’s celebratory atmosphere in the following months, with Christmas, New Year and Chinese New Year approaching.

By learning from the improvements from Grenfell recovery process, Hong Kong can support a more equitable, healing-focused recovery for Tai Po's affected families and the wider community:

Prioritize long-term, culturally adapted services (e.g., multilingual support) to address stigma and barriers. Consistent mental health support for adults and children in Tai Po may be needed for an extended period as well, as seen in how Grenfell residents and children have continued to access these services over the years. Continued care is especially important for those who may not recognize the long-term impact of the trauma, and for children whose symptoms can emerge later, so that issues arising later can be identified and treated. Listening to community voices to identify service gaps also increased uptake of mental health support amongst Grenfell residents, and decreasing barriers to access their financial assistance also enhanced their sense of control.

Foster transparent communication on resettlement and investigations to rebuild trust and minimize helplessness. The lack of transparency while investigating the Tai Po fire could cause re-traumatization and increase feelings of hopelessness. How the government handles rehousing for displaced residents will also be crucial. In parallel with the Grenfell aftermath, although many households there were rehoused, a significant number later sought to move again or had already relocated by early 2024. Reasons included a sense of lost community and a lack of psychological safety in the provided housing, reflecting distrust resulting from the fire. This simply leads to further disappointments, insecurity, and loss of resources.

Promote community resilience through self-care alternatives (e.g., community-led initiatives like peer groups or traditional activities) alongside formal care. Community-led recovery projects have improved well-being for those affected in Grenfell in a cost-effective manner. These initiatives create spaces for people to come together, offer purpose through learning new skills, and restore a sense of control over lives disrupted by the tragedy. This is particularly useful for sectors of the community where mental health service utilization isn’t embraced.

If you have been directly or indirectly affected by the Tai Po fire, feel free to contact us for more information on how counselling can help. There are also many other mental health resources in Hong Kong that can help with working through trauma for yourself or for your children.

中文摘要

2025年大埔火災除了造成人員傷亡、財產損失與大規模疏散外,更可能在長期內影響社區與倖存者的精神健康。雖然居民在事發後獲得了即時援助,但隨之而來的挑戰仍包括重新安置的壓力、經濟負擔,以及工作與學業的中斷。若參照2017年英國倫敦格倫費爾大樓火災的經驗,災後心理影響往往持續多年,常見問題包括焦慮、抑鬱、睡眠障礙與持續性哀傷。研究顯示,格倫費爾約有三分之二的居民(67%)在事發後面臨創傷後壓力症候群(PTSD)的高風險,而兒童與青少年則出現恐慌、退化行為或激躁行為的增加。

英國的經驗亦指出,當心理服務受到污名化或語言與文化障礙的限制時,部分居民會不願或無法尋求輔導。更嚴重的是,格倫費爾居民因政府在災前忽視安全訴求、災後反應遲緩而失去信任,進一步加深了心理創傷。相對之下,社區自發的行動卻成為復原的重要力量,例如 Grenfell United 的倡議,以及居民自組的烹飪班、瑜伽課、默哀步行等活動,都強化了社區的凝聚力與互助精神。

香港可以從中得到啟示:首先,必須提供符合大埔居民需要的長期心理支援,亦要減少污名。其次,大火調查與安置過程中應保持透明,避免居民感到無助或遭受二次傷害。第三,鼓勵社區自助與各類活動,讓居民在互動中重建信任與力量。最後,特別需要持續關注兒童與青少年的心理狀況,因為他們的創傷反應可能延遲出現。

總而言之,災後復原不僅是物質上的安置,更是心理與社區的長期重建。若香港能結合格倫費爾的經驗,推動透明、公平與合適的支援,將更有助於大埔火災受影響家庭的康復,以及社會信任的重建。

如果你曾直接或間接受到大埔火災的影響,歡迎與我們聯絡,以了解輔導如何能夠提供幫助。香港亦有許多其他心理健康資源,可以協助你或你的孩子處理創傷並逐步復原。